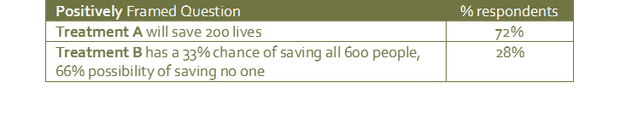

How framing can change everythingAs project managers we spend a lot of time asking questions. It is important that we understand that how we ask a question can have a profound influence on the answer we will be given. When we ask a colleague for a progress update, or to assess a risk, or even to let us know whether they are happy with the manner in which the project is being managed we are providing information, in the form of the words that we use, which may influence the answer that we receive. Framing effect The framing effect is a type of cognitive bias where people can be influenced into giving different answers depending on how a question is presented. Some of the most interesting examples of the framing effect can be found when decisions are being made about risk and it is for this reason that a basic understanding of this psychological phenomenon is crucial for project managers and business executives. The prevailing theory suggests that people are more wary of risks when a positive frame is presented but are more accepting of risks when a negative frame is presented. To better understand what this means in practise, consider this example from a paper published by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman1 in 1981: The study looked at how different question phrasing affected participants’ decisions in a hypothetical life and death scenario. The participants were asked to choose between two medical treatments for 600 people who had been affected by a lethal disease. The treatment options were not without risk. Treatment A was predicted to result in 400 deaths, whereas treatment B had a 33% chance that no one would die but a 66% chance that everyone would die. This choice was then presented to the participants in two different ways; one with ‘positive framing’ - how many people would live, the other with ‘negative framing’ - how many people would die. The results were as follows: Treatment A was chosen by 72% of respondents when it was framed positively, but treatment B becomes the overwhelming preference in the negative frame, demonstrating that people are much more accepting of risks when the decision is framed negatively. Of course, in this example, there was no material difference between the risks involved in either treatment! Fooled by framing – always ‘do the math’ Question framing can also be the cause of curious cognitive difficulties. For example, we are easily confused by questions that are framed using inappropriate units of measure. Consider the following:

The answer to the question seems obvious; both Margo and Jake are driving 10,000 miles per year. Margo is only going to achieve an additional 2 miles per gallon whereas Jake is going to improve his consumption by 10 mpg. It seems that we don’t even have to ‘do the math’ – Jake is clearly going to be the winner and save the most. Except he isn’t, Margo is. We have to do the math. In driving 10,000 miles in her new Mustang, Margo uses 714 gallons of fuel. Previously her gas-guzzling Corvette used 833 gallons to cover the same distance. So she’s saved 119 gallons in her first year. Jake, on the other hand, will save only 83 gallons. His old Volvo used 333 gallons to cover 10,000 miles and his new, improved, Volvo will use 250. So although Jake’s fuel consumption has reduced by 25% and Margo’s by only 14%, Margo is still ahead in terms of savings. This is because her cars are so inefficient in comparison to his that a mere 14% improvement is still a lot more fuel! Most people are caught out by the question so don’t feel too bad if you were too. But the more interesting discovery is this: if the question is re-framed so that instead of presenting the fuel consumption measure as miles per gallon it was shown as gallons per mile, we would instantly see that Margo was going to save the most fuel. Try it. When discussing business issues involving KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) we should always bear in mind the importance of framing and measures. The health of a business (or of a project for that matter) is often communicated to stakeholders in the form of KPIs. You will be familiar with system dashboards that show, for example, sales growth, sales per employee, percent of target reached, debt to equity ratio, margin by product etc. When reviewing this sort of data while discussing KPIs, bear in mind that perception of performance can be profoundly influenced by the measures used. You may not want to promote Jake as a result of his upgrade decision, after all, Margo did save the company the most money! The Challenger Shuttle Disaster Every now and again a project failure occurs which is so devastating that it attracts the attention of the entire world. On January 28, 1986 the NASA space shuttle, Challenger, took off from a launch pad at Kennedy Space Centre. 73 seconds later it exploded instantly killing its crew of seven. The night before the launch a number of engineers at NASA contractor, Morton Thiokol, had tried to stop the launch on safety grounds. Their analysis of the weather conditions and their understanding of the temperature sensitivity of the booster rockets’ hydraulic systems had a resulted in the assessment that it was too risky to proceed and that the launch should be delayed. The management team asked the engineers to reconsider and to look at the potential costs, both financial and in Public Relations terms, of the launch not proceeding. The managers set out a number of factors for the engineering team to consider including the fact that President Ronald Reagan was set to deliver a State of the Union address that evening and was planning to tout the Challenger launch. The engineers reconsidered. With the question now re-framed to highlight the negative consequences of not launching they eventually agreed that the launch should proceed. NASA’s management team had succeeded in changing the frame of the question so that the cost of not launching carried more weight than the risk of launching. Despite it being the coldest weather Kennedy Space Centre had ever experienced for a shuttle launch, it went ahead. It seems that the engineers were very wary of the risks when the launch was presented in a positive frame but were persuaded to be more accepting of the risks when they were set out in a negative frame. This tragic example highlights how even the most experienced and qualified professionals can be influenced to assess hazards differently when the risks are framed in a certain way. This is not to understate the immense pressure the engineers faced from their superiors (who had a vested interest in achieving the launch date). The lesson for project managers is that if this can happen at NASA it can happen in any project. The more we understand about how people arrive at their assumptions with regard to risk, the more we can do to ensure that their conclusions are logical and rational.

3 Comments

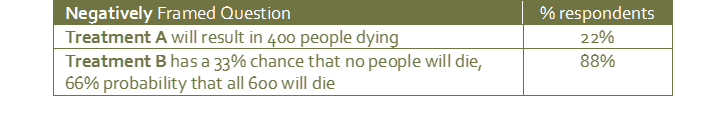

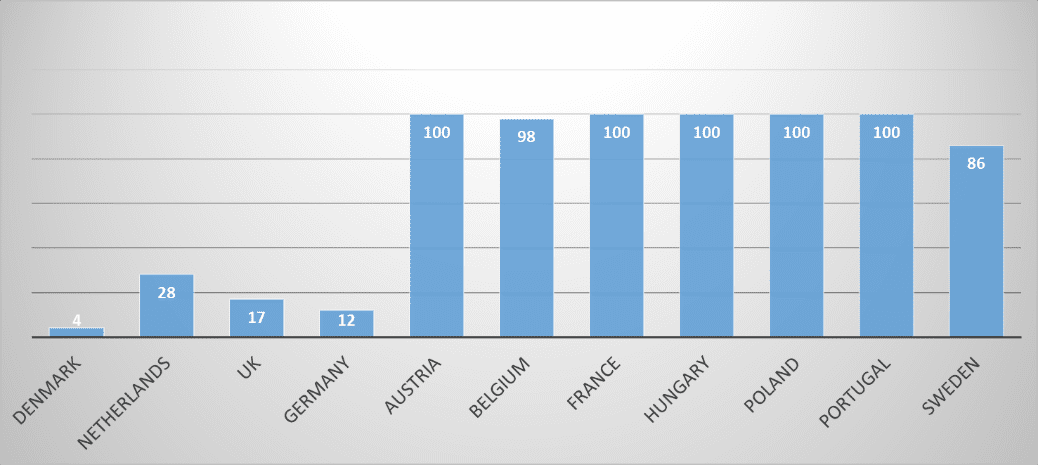

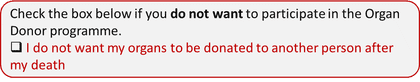

How we are prone to making bad decisionsAs project managers we are used to making decisions and most of us would acknowledge that the ability to make the right decisions at the right time is one of the most important factors influencing the outcome of a project. Of course, not all of our decisions turn out to be the right ones, we are only human after all, but we’d like to think that we make more correct decisions than we do wrong ones. More importantly, we like to think that we get the big decisions right most of the time, so we pay special attention to mission-critical aspects of the project such as risk management, task estimates, team selection and milestone planning to ensure that we make them logically and rationally. But what if making rational and logical decisions is more challenging than we think? What if our choices could be influenced in one direction or another without our even realising it? Let us step out of the world of project management for a moment and into an environment that will be instantly recognisable: the supermarket. You may be familiar with product price labels that look something like this: Sauvignon Blanc Was £7.99 Now £4.99 And despite our best efforts to employ our critical faculties, when we see a label with this sort of offer we cannot help but think that we would be buying a premium product at a discounted price. Retail marketing and product placement gurus have long understood how important and influential our desire to make comparisons is to the decision-making process. The technique is employed in many situations which the supermarkets hope will assist us in making the ‘right’ decision but which actually highlight just how irrational our decision-making can sometimes be. Consider the following set up: When presented with three comparable products at different price points most of us tend to pick the mid-price product. Some of us may pick the cheaper or the more expensive options and these choices will be influenced by a number of very rational considerations including how wealthy we feel and what our standards and quality expectations might be. However, an interesting phenomenon occurs when a fourth product is included in the selection: Research has shown that when another, more expensive, option is introduced, a significant number of shoppers who previously would have bought the mid-price product instead opt for the next most expensive one. Somehow the addition of a premium option – which is usually significantly more expensive – tricks us into thinking that the next most expensive product offers the best value for money. If we were happy to spend a certain amount on a bottle of wine, why should the addition of a very costly bottle to the shelf cause us to change our minds and spend more money? This does not seem rational, but the example does provide a clue about the processes that our brains employ when making comparative decisions. Comparisons, relativity and default settings In his ground-breaking 2008 book Predictably Irrational, Dan Ariely showed how easily a person’s choices could be manipulated without their being aware. In a chapter entitled The Truth About Relativity he introduces a concept known as the ‘Decoy Effect’ using an example like this one: You are offered two options for a romantic vacation for two; a free, all-expenses paid trip to Paris or an equivalent all-expenses paid trip to Rome, which would you choose? Your answer would most likely depend upon your preferences in terms of art, culture, food and entertainment. Some people may opt for Paris and some for Rome and in a large enough sample group we might expect the split to be about half and half. However, if a third option is added, in this case also a trip to Rome but without a free breakfast included, a strange thing happens: more people choose the all-expenses paid trip to Rome over the all-expenses paid trip to Paris. No one chooses the inferior trip to Rome without breakfast, of course, but why does the presence of a third, inferior option cause people to gravitate towards Rome rather than Paris? The explanation may be that the presence of a ‘decoy’ makes it easier to compare the two options for Rome than to compare Paris with Rome. This decoy effect (also called the asymmetric dominance effect) is a phenomenon that causes people to have a change in preference between two options when presented with a third option that is related to, but also markedly inferior to, one of the original options. The presence of a decoy option results in an irrational decision. In this case Rome now looks like a better option than Paris despite no new information about Rome or Paris becoming available to the consumer. This kind of irrational decision making is not limited to the ordinary consumer; it is apparent that we are all prone to subconscious influence by decoys. Even expert professionals, when evaluating critical decisions, are susceptible to making illogical choices. In a study carried out in 1995, researchers Donald Redelmeier and Eldar Shafir illustrated how experienced medical doctors could, under certain conditions, be influenced into selecting an inferior treatment course for patients suffering from chronic pain: The first scenario presented to the doctors was as follows: You are reviewing the case of a patient who has been suffering from hip pain for some time and has already been scheduled for a hip replacement. However, while examining the case notes ahead of the surgery you realise that you have not yet tried treating the patient with Ibuprofen. What should you do: (a) leave the patient to undergo the surgery, or, (b) delay the operation until a course of Ibuprofen has been undertaken? In most cases (you will be pleased to know) the doctors delayed the surgical intervention and recommended that the patient be prescribed a course of Ibuprofen. In the second scenario, another group of physicians was presented with a similar case but this time they were told that two different medications had yet to be tried: Ibuprofen or Piroxicam. This time, most physicians opted to allow the patient to continue with the hip replacement! It seems that because another decision factor was added and the choice made more complex, many more doctors allowed the default option to stand. To better understand this example it is important to realise the role played by the default option. We need to bear in mind that the patient was already scheduled to have a hip replacement. The choice was not ‘Which of these many treatment options is best?’ but rather ‘Do I make the decision to change the current course of action in order to try something different?’. It appears from numerous experiments like this one that if multiple or complex choices are available then the tendency is to leave things as they are. Only when a simple alternative is presented is it likely to be selected – even if the alternative choice would have been the more logical thing to do. As a project manager and business owner I have seen decision situations like these arise many times. While directing a large ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) system installation some years ago my implementation team was presented with a sudden resourcing crisis after half of our implementation consultants were removed from the project at short notice. With the scheduled ‘go-live’ three months away and with little prospect of completing all of the application testing and user training in time we were faced with a simple decision: (a) should we proceed with the project as planned and hope that, by redoubling our efforts and with a fair wind (and some luck), we are able to deliver a workable system, or, (b) do we change the scope of the project so that only a subset of the overall functionality is delivered to begin with, and thereafter initiate a new project to implement the remaining features. At a core team meeting we discussed both courses of action in detail and decided on the latter option: to reduce the scope of the project in order to meet the scheduled date, albeit with a reduced set of system functions. I duly presented this as my recommendation to the CEO of the business at the next project board meeting. There was much discussion between the various stakeholders after which another option was suggested: why not recruit implementation specialists from outside of the business so that the go-live date could still be met without the scope of the project being reduced? I didn’t relish the thought of trying to find a handful of consultants with the appropriate expertise in our chosen ERP application at short notice, but I agreed to take the idea back to the core team for further consideration. The core team representatives now discussed the three options and very quickly arrived at a decision: the team preferred to redouble their efforts, plough on, and hope for the best. I was astounded! It seemed that the complexity of the decision-making process had now increased to the point where it was just too difficult to weigh up the pros and cons of each option. No one knew how best to go about recruiting additional implementors and some members of the team decided to reconsider the feasibility of dropping some functional elements from the scope. The easiest option seemed to be to do nothing, and to let the project unfold according to its original schedule, in other words, to accept the default position. What originally seemed like a simple decision had turned into a complex one by the addition of a challenging, third option. The validity of the choice to proceed with a reduced scope had not altered, but the team’s perception of the choices available had changed significantly enough for them to retreat and backtrack. (Of course, for the record, I did not allow the decision to stand, but that’s not the point of the story.) Dan Ariely provides another salient example of the importance of default options in a case study featuring an analysis of Organ Donor programmes in Europe from 2009. The chart above shows the percentage of the eligible population who agreed to carry an organ donor card when applying for their driving license. On the left of the chart are the countries with the lowest participation rate: Denmark, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom* and Germany. On the right are the countries which subscribe to the scheme on an almost universal basis. It is worth noting that in order to persuade its population to carry more donor cards, the Dutch government wrote a personal letter to every single eligible citizen and asked each one to participate in the scheme. The result was a significant uptake in membership to 28%. It is not obvious from an initial analysis of the data why there should be such a marked variation between countries. Cultural and social differences do not seem to explain it, after all, one would expect Germany and Austria to have similar values, and it is hard to imagine attitudes in the Netherlands being dramatically different from, say, Belgium. But participation in the organ donor scheme is dramatically different between these countries. So why do only 4% of Danish drivers carry organ donor cards when 86% of their near neighbours in Sweden carry them? The answer lies not in the ethical or moral attitudes of the respective populations but in a simple administrative oversight. The countries with the poorest participation in the scheme provided driving license applicants with a form containing the following question: Whereas the countries with the best participation in the scheme used the following question: In both cases the default option is to do nothing by not ticking the box. By doing nothing in the first case you opt out of the scheme, by doing nothing in the second case you opt in to the scheme.

When faced with a choice, people are strongly drawn to the default option, the default option usually being the one that requires the least effort or consideration. That this sort of question framing should influence people’s decision-making to such a degree is fascinating to say the least, especially so given the nature of the choice being made in this particular example. It also raises an important question: if framing can so easily influence us when it comes to making such important decisions, then how easy must it be to sway us when we don’t perceive the stakes to be so high? * From 1st December 2015 the system in England & Wales was changed to an ‘opt-out’ for this very reason |

AuthorThe Irrational Project Manager Archives

January 2017

Categories

All

|