|

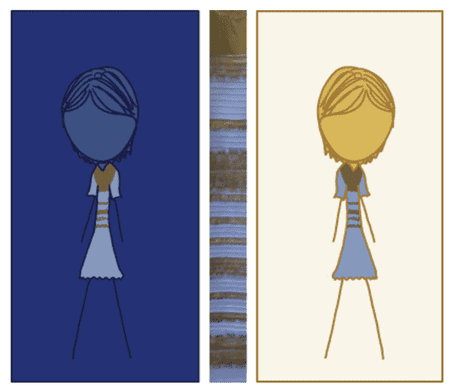

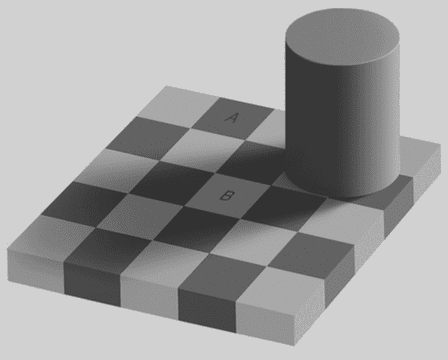

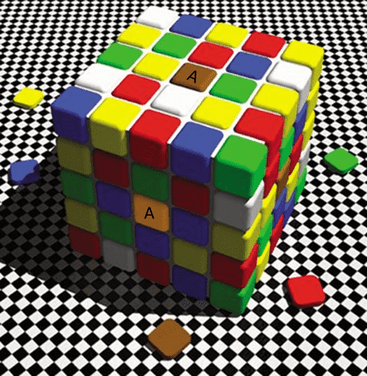

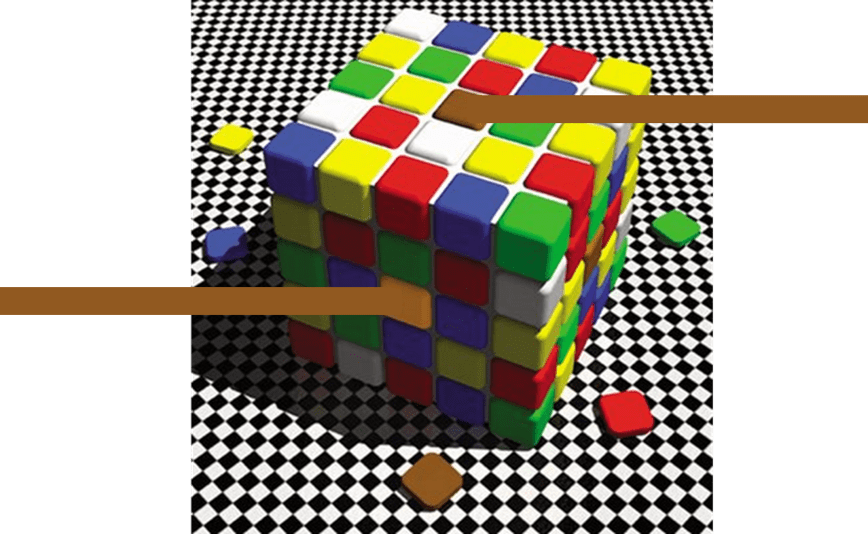

You wanna bet? Most of us don’t go about our business as Project Managers assuming that we are irrational, biased or easily fooled. Quite the opposite, in fact. We feel that we make decisions based on reason, cold analysis and a rational assessment of the available evidence. We believe that one of the skills that makes a Project Manager good at their job is the ability to make thoughtful, coherent and balanced decisions most of the time, in any given situation, irrespective of stress levels, pressure from stakeholders, looming deadlines or stretched resources. But whether we realise it or not, our decisions are often skewed or biased or just downright wrong because we regularly fall prey to cognitive biases, subconscious influences and things that psychologists like to call decision traps. Of course, in everyday life most of us manage OK. We usually don’t see the effects of our irrational tendencies, and in fact, there is evidence that the short-cuts or heuristic thinking processes that we use day-to-day evolved in the past to improve our ancestors’ survival chances. But these evolutionary adaptations of our brains took place a million years ago, when homo sapiens needed very different skills and abilities to survive. So what about now, how does this legacy of mental capability affect us in our modern work lives? What if our inability to think and act rationally impacts the decisions that we take while we’re engaged in our business of project management? Is it conceivable that some of the problems we face when coordinating teams, assessing risk, estimating tasks, devising schedules or communicating with stakeholders could be down to errors in the way that our brains actually work? If you’re anything like me you’re probably thinking “Well, I can see how that might be an explanation for the issues some of my colleagues face, but I don’t think it applies to me, I’m fairly sure that I approach things in a pretty rational way, I’m a ‘reason and logic’ kind of person, I don’t think I’m easily fooled or misled.” And you may well be right, but statistically it’s unlikely, for reasons that I explain more fully in this book. (See the chapter No one is immune). For now, let’s look at a couple of simple examples that might just catch you out. In the preface to his best-selling book Inevitable Illusions, Massimo Piatelli-Palmarini illustrates just how easily we find ourselves believing bizarrely incorrect facts without realising it, indeed, without giving these ‘facts’ much forethought at all. He uses examples from geography to illustrate what he likes to refer to as mental tunnels. Here are a couple of them to think about; Losing my sense of direction These examples work best for people with a basic knowledge of the geography of the United States, Italy or the United Kingdom. Let’s start with the American example: Imagine you’re in Los Angeles and you take off in a helicopter to head to Reno, Nevada. What direction do you think you would need to fly in? Most people, even most Californians, guess that it would be North and East, perhaps a heading of 10 or 20 degrees East. (Don’t look at a chart just yet.) Now, for the Brits, imagine again taking off in a helicopter from Bristol. If you head immediately North and fly towards Scotland what major Scottish city would you end up flying over first? If you’re a Londoner, imagine taking off from Heathrow and heading directly North, what is the first Northern English city you’d fly over? The prevailing answers are Glasgow and Leeds, respectively. But, as you might suspect, they are entirely incorrect, as is the answer that most Americans give in response to the Reno question. The correct answers are as follows; Reno is actually North and West of Los Angeles, 20 degrees West to be precise. The first city you’d fly over if you were heading North from England’s ‘West Country’ city of Bristol is actually Edinburgh on Scotland’s East Coast. Similarly flying due North from London has your helicopter passing Hull on the left before crossing the coast onto the North Sea. You’d barely get within 100 km of Leeds. Native born Italians are used to seeing the map of Italy drawn at an angle running from North West to South East, but even so they are generally fooled into thinking that Trieste is some 20 or 30 degrees East of Naples, it being on Italy’s Eastern border with Slovenia and Naples being on the West Coast. But, of course, they’d be wrong. Trieste is, in fact, just West of Naples. Now you can check these out on the charts, Google Maps will do. While you’re at it amaze yourself with these other facts: the first country you’d fly over if you headed directly South from Detroit is Canada. Rome is North of New York City. Don’t be disappointed if you answered all of these questions incorrectly, most people do. It’s not because you’re bad at geography or because you don’t know your East from your West. The actual explanation is that your mind played a trick on you. Without your knowing, your brain rotated the mental image of these maps to align any more-or-less vertical land masses with a North South axis. No one fully understand why this is, we don’t know, for example, why no one rotates the land mass of Italy horizontally, it’s always straightened vertically in our minds, as are the British Isles and the Western Coastline of the United States. Piatelli-Palmarini refers to these as cases of tunnel vision and I’m indebted to him for these examples. They illustrate very elegantly how our brains sometimes work on a problem in our subconscious and present us with false conclusions without our even realising it. But these instances are relatively benign and need not alarm us unduly. For more examples that perhaps ought to alarm us, read on. Do your eyes deceive you? If we’re fortunate enough not to suffer from a serious visual impairment, we probably trust our eyes more than any of our other senses. They are generally in use from the minute we wake up to the time we close them again to go to sleep. Most of us are highly resistant to the idea that our vision might regularly play tricks on us, even though we’ve seen stage magicians fool people on television many times, we have an almost unshakable faith on our own ability to discern reality from illusion. So what colour was that dress? If you pay attention to such things, you may remember a furore in social media about a celebrity whose dress appeared as to be different colours to different people? Some thought it was black and blue, others white and gold. I recall asking myself at the time how could it possibly be that different people had an entirely different impression of the same photograph. I wondered if it was their eyes or their brains that were interpreting the visual data differently. In the example below there are two images of a woman wearing a dress. Do they appear to be the same colour to you? For most observers, the dress on the left is a shade lighter than the one on the right. Similarly, the olive brown colour at the top of the dress is slightly darker on the right than it is on the left. The two dresses are, in fact, exactly the same colour. But it doesn’t seem to matter how long you stare at the picture, even if you believe it to be true you can’t force your eyes to see them as being identical. The blue and brown on the left hand dress always seems lighter than the one on the right. All good project managers are somewhat skeptical in nature (and you have every right to be) so for those of you who don’t believe it, here is a modified version of the picture to help you convince yourself of the facts of the matter. Fifty Shades of Grey? In another well-known version of a related visual illusion we see two squares, in this case labelled A and B, which are clearly different shades of grey. You would probably find it very difficult to believe that the squares are exactly the same colour and that your eyes – or more correctly your brain – is fooling you into thinking that one is lighter than the other? And yet that’s precisely what you’re not seeing. In this example of the shadow illusion squares A and B are identical in both colour and shade. Yet knowing that this is true is of no help when you try to see them as the same colour. The presence of the cylinder casting an apparent shadow over a chequer board helps to fool your brain into creating a visual perception of the squares in which square A is significantly and obviously darker than square B. In fact, the only way you can be convinced that they are the same colour is if you completely mask out the other parts of the image to reveal only the two squares in question. Try printing this blog page and cutting squares A and B out then laying them side by side, I promise you that you'll be amazed. Rubik’s Magic Cube The final example is perhaps the most astonishing of all. Below is an illustration of a 5- row version of Ernő Rubik’s famous cube. Two squares are highlighted, A, I think you already know what’s coming ... Yes, the ‘yellow’ square A and the brown square A are actually the same colour, and it’s brown. The illusion is exquisite in that your brain has made the square on the shaded face of the cube yellow. But it’s not, it is in fact, brown, (R145 G89 B32 to be precise). The bars extending out to the side of the squares in the version of the illustration below helps us to see the colours as they ‘really are’, but take care, if you permit your eyes to wander back towards the centre of the picture you may notice the bar on the left lighten again, and by the time you find yourself looking at the lower square it may even look yellow once more! Although we may use the expression ‘our eyes have deceived us’ we know that it is, in fact, our brains that are the cause of the problem. Our eyes are the just the sensors that detect electromagnetic radiation in the visible spectrum and convert it into electrical impulses. These electrical stimuli are then sent along the optic nerve to the visual processing part of the brain. This is the primary visual cortex — a thin sheet of tissue located in the occipital lobe in the back of the brain.

Thanks to technological advances such as fMRI scanning, we now know that different areas of the brain deal with different aspects of visual interpretation such as colour, shape, lines and motion. Just how the brain deciphers this information to present us with our experience of the ‘real world’ remains poorly understood. It would seem that our brains have a lot to answer for, and, as project managers, visual illusions are the probably the least of our concerns. Yet they serve as useful metaphors for the challenges that our brains face when trying to make sense of the complex world we live and work in, a reminder that we need to be constantly vigilant if we are to avoid being fooled.

4 Comments

|

AuthorThe Irrational Project Manager Archives

January 2017

Categories

All

|