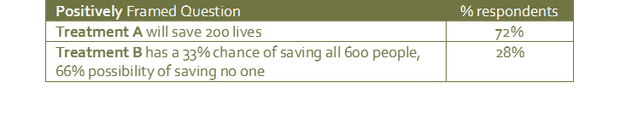

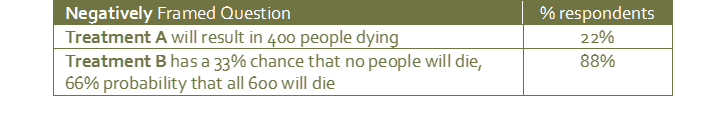

How framing can change everythingAs project managers we spend a lot of time asking questions. It is important that we understand that how we ask a question can have a profound influence on the answer we will be given. When we ask a colleague for a progress update, or to assess a risk, or even to let us know whether they are happy with the manner in which the project is being managed we are providing information, in the form of the words that we use, which may influence the answer that we receive. Framing effect The framing effect is a type of cognitive bias where people can be influenced into giving different answers depending on how a question is presented. Some of the most interesting examples of the framing effect can be found when decisions are being made about risk and it is for this reason that a basic understanding of this psychological phenomenon is crucial for project managers and business executives. The prevailing theory suggests that people are more wary of risks when a positive frame is presented but are more accepting of risks when a negative frame is presented. To better understand what this means in practise, consider this example from a paper published by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman1 in 1981: The study looked at how different question phrasing affected participants’ decisions in a hypothetical life and death scenario. The participants were asked to choose between two medical treatments for 600 people who had been affected by a lethal disease. The treatment options were not without risk. Treatment A was predicted to result in 400 deaths, whereas treatment B had a 33% chance that no one would die but a 66% chance that everyone would die. This choice was then presented to the participants in two different ways; one with ‘positive framing’ - how many people would live, the other with ‘negative framing’ - how many people would die. The results were as follows: Treatment A was chosen by 72% of respondents when it was framed positively, but treatment B becomes the overwhelming preference in the negative frame, demonstrating that people are much more accepting of risks when the decision is framed negatively. Of course, in this example, there was no material difference between the risks involved in either treatment! Fooled by framing – always ‘do the math’ Question framing can also be the cause of curious cognitive difficulties. For example, we are easily confused by questions that are framed using inappropriate units of measure. Consider the following:

The answer to the question seems obvious; both Margo and Jake are driving 10,000 miles per year. Margo is only going to achieve an additional 2 miles per gallon whereas Jake is going to improve his consumption by 10 mpg. It seems that we don’t even have to ‘do the math’ – Jake is clearly going to be the winner and save the most. Except he isn’t, Margo is. We have to do the math. In driving 10,000 miles in her new Mustang, Margo uses 714 gallons of fuel. Previously her gas-guzzling Corvette used 833 gallons to cover the same distance. So she’s saved 119 gallons in her first year. Jake, on the other hand, will save only 83 gallons. His old Volvo used 333 gallons to cover 10,000 miles and his new, improved, Volvo will use 250. So although Jake’s fuel consumption has reduced by 25% and Margo’s by only 14%, Margo is still ahead in terms of savings. This is because her cars are so inefficient in comparison to his that a mere 14% improvement is still a lot more fuel! Most people are caught out by the question so don’t feel too bad if you were too. But the more interesting discovery is this: if the question is re-framed so that instead of presenting the fuel consumption measure as miles per gallon it was shown as gallons per mile, we would instantly see that Margo was going to save the most fuel. Try it. When discussing business issues involving KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) we should always bear in mind the importance of framing and measures. The health of a business (or of a project for that matter) is often communicated to stakeholders in the form of KPIs. You will be familiar with system dashboards that show, for example, sales growth, sales per employee, percent of target reached, debt to equity ratio, margin by product etc. When reviewing this sort of data while discussing KPIs, bear in mind that perception of performance can be profoundly influenced by the measures used. You may not want to promote Jake as a result of his upgrade decision, after all, Margo did save the company the most money! The Challenger Shuttle Disaster Every now and again a project failure occurs which is so devastating that it attracts the attention of the entire world. On January 28, 1986 the NASA space shuttle, Challenger, took off from a launch pad at Kennedy Space Centre. 73 seconds later it exploded instantly killing its crew of seven. The night before the launch a number of engineers at NASA contractor, Morton Thiokol, had tried to stop the launch on safety grounds. Their analysis of the weather conditions and their understanding of the temperature sensitivity of the booster rockets’ hydraulic systems had a resulted in the assessment that it was too risky to proceed and that the launch should be delayed. The management team asked the engineers to reconsider and to look at the potential costs, both financial and in Public Relations terms, of the launch not proceeding. The managers set out a number of factors for the engineering team to consider including the fact that President Ronald Reagan was set to deliver a State of the Union address that evening and was planning to tout the Challenger launch. The engineers reconsidered. With the question now re-framed to highlight the negative consequences of not launching they eventually agreed that the launch should proceed. NASA’s management team had succeeded in changing the frame of the question so that the cost of not launching carried more weight than the risk of launching. Despite it being the coldest weather Kennedy Space Centre had ever experienced for a shuttle launch, it went ahead. It seems that the engineers were very wary of the risks when the launch was presented in a positive frame but were persuaded to be more accepting of the risks when they were set out in a negative frame. This tragic example highlights how even the most experienced and qualified professionals can be influenced to assess hazards differently when the risks are framed in a certain way. This is not to understate the immense pressure the engineers faced from their superiors (who had a vested interest in achieving the launch date). The lesson for project managers is that if this can happen at NASA it can happen in any project. The more we understand about how people arrive at their assumptions with regard to risk, the more we can do to ensure that their conclusions are logical and rational.

3 Comments

|

AuthorThe Irrational Project Manager Archives

January 2017

Categories

All

|